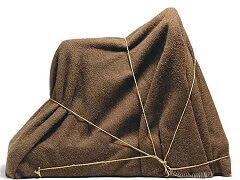

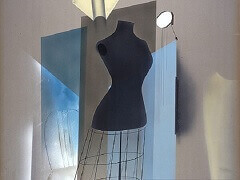

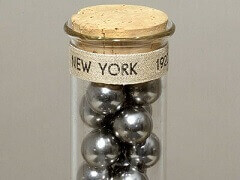

The Enigma of Isidore Ducasse, 1920 by Man Ray

The Enigma of Isidore Ducasse, 1920, remade 1972, consists of a sewing machine, wrapped in a blanket and tied with string. Man Ray's idea of using a sewing machine was inspired by a simile used by the French writer, Isidore Ducasse (1809-87), better known as the Comte de Lautréamont, 'Beautiful as the accidental encounter, on a dissecting table, of a sewing machine and an umbrella'. It was a phrase that was greatly admired by the writers in Paris with whom Man Ray was close friends and who formed the nucleus of the Paris dada and later surrealist groups. They saw it as paradigmatic of a new type of surprising imagery, as well as replete with disguised sexual symbolism. (The umbrella was interpreted as a male element, the sewing machine as a female element, and the dissecting table as a bed.). Man Ray's wrapped object, however, was a mystery, and suggested not so much a sewing machine as some utterly undefined, and therefore potentially more disturbing, presence. The word 'enigma' in the title echoed some of the titles of paintings by Giorgio de Chirico (1888-1978), also much admired by the proto-surrealist group, while its image of something wrapped and hidden can be seen as a forerunner of images of disguised or concealed objects by the Belgian surrealist René Magritte (1898-1967), as well as the later wrapped works of Christo (born 1935).

A photograph of the original version of the work was reproduced on the first page of the first issue of the surrealist periodical La Révolution surréaliste in December 1924. The accompanying text was a manifesto statement about the importance of dreams within surrealism. It would seem that the photograph of this mysterious object had been selected to encapsulate the surrealists' vision of what lay beyond rational apprehension and the norms of daily reality. In 1932 the surrealist painter Max Ernst recalled this particular image when he wrote about the early days of the movement: 'The semi-darkness of the first phase of surrealist experiment would disclose some headless dummies and a shape wrapped up and tied with string, the latter, being unidentifiable, having seemed very disturbing in one of Man Ray's photographs (already, then, this suggested other wrapped-up objects which one wanted to identify by touch but finally found could not be identified; their invention, however, came later).'

Despite Man Ray's status as one of the pioneering figures of interwar art, his objects are not particularly widely known. This is largely due to his greater fame as a photographer; but it is also in part due to the complex history of many of his objects. A number of the earliest works were lost or accidentally destroyed (the same is true of many of the early classic objects by his friend Marcel Duchamp, 1887-1968). Others are known primarily as photographs reproduced in surrealist magazines and their status as objects has been obscured by the celebrity of the photographic images. In fact, Man Ray sometimes made objects in order to photograph them, and then discarded them, or reused them in other ways. He also remade some works, thereby creating new originals, and when, in the 1960s and 1970s, there was a greater commercial interest in the objects, he, like Duchamp, arranged for some of his objects to be produced in editions.